ABORIGINAL ROCK ART

BACK

Although rock engravings and paintings are found throughout Australia, at present there is no direct method for dating them. Some are apparently of great antiquity. Engravings with evident

heavy weathering depict motifs unknown to modern tribal Aborigines. The earliest firm date so far obtained is at the Early Man rock shelter in the far north of Queensland. Here, simple designs have been pecked out of the wall below an occupation level dated to 13,000 years.

Evidence has been found to infer that rock painting is of a similar antiquity to the engravings. Pieces of ochre displaying characteristic age wear have been found in a 19,000 year old level at Naulabila in the Northern Territory. Throughout Arnhem Land there are thousands of painted rock shelters in some of which the paintings are covered with a siliceous (or glassy) skin. It is thought that these skins do not form under present climatic conditions, and the last period when the process could have taken place occurred during the coldest phase at the end of ice age, about 20,000 years ago.

Aboriginal art is essentially a reflection of nature. The Aborigines devised a system by which unfamiliar and unknown things in their environment could be explained. This involved attributing human characteristics to these unknown forces of nature. Their world therefore abounded with supernatural and mythical beings whose doings were manifested in everything about them. Such beings were at the heart of the Dreaming.

The permanence of Aboriginal life was ensured by the invoking of powerful forces through the symbolism effort. Thus rock art was a way of tapping the power of the spirit beings so as to maintain the fertility of the land and all the creatures that dwelt in it.

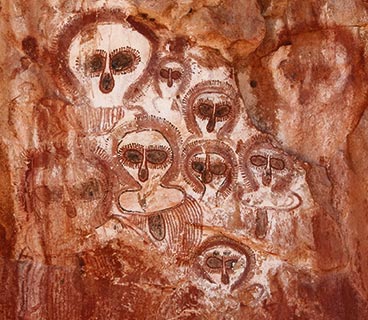

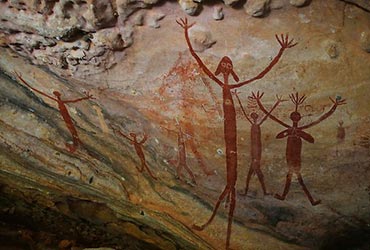

The great diversity of recent Aboriginal culture is reflected in the very different art styles found in different part of Australia. Dr. Josephine Flood, an archaeologist with the Australian Heritage Commission, has surveyed the range of art styles and the following is based upon her work. Tasmanian rock art is virtually all engravings, whereas that of Victoria is almost all paintings. So far, in Victoria, sixty-nine painting sites have been found, mostly in the Grampians (see below). In New South Wales engraving and paintings are both represented, and in the outback Cobar region ‘small, lively, red and white figures dance across the walls of dozens of shelters’ (see below). In the coastal Hawkesbury sandstone country paintings are larger and include marine subject, and around Sydney there are thousands of outline engravings, whose subjects from whales to lyre birds, and from dingoes to sailing ships. In Western Australia the Pilbara region contains the high point of Australia rock engraving. Figures with human characteristics ‘are often placed in tiers high on pyramidal piles of huge boulders, where they look out … across the featureless sand plains’. The Kimberleys is famous for the visual splendour of its colourful Wandjina figures (see below). These replaced an earlier style of ‘Bradshaw’ figures which are akin to the early ‘dynamic’ or ‘mimi’ figures of Arnhem Land.

Much better known is the elaborate x-ray stile of the late Arnhem Land paintings, which the skeleton and internal organs of creatures are portrayed as well as external features (see below). The rock art of Queensland is different again. The Cape York peninsula contains one of the most colourful and prolific bodies of rock art in the world; enormous naturalistic figures of animals, birds, plants, humans, and spirit figures adorn the walls of hundreds of rock shelters (see below). In contrast, in the Central Highlands of southern Queensland stencil art is highly developed with the white sandstone walls covered in silhouettes red, yellow and black.

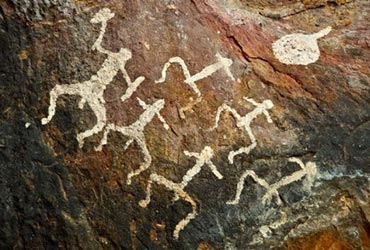

ABORIGINAL ROCK ART. STICK FIGURES-COBAR REGION, NEW SOUTH WALES

Through the same semi-arid Cobar region in outback New South Wales, the Darling River wings upon plains lightly covered with white pine, mallee, mulga and the occasional large kurrajong. Temporary water holes and soaks occur intermittently throughout the low ranges and it is from rock shelters around one of these water holes that the painting comes.

The scene depicted shows stick figures, probably in the posture of ceremonial dancers with their legs bowed and arms raised; some appear to be holding a boomerang of shield. These paintings were most probably executed by finger painting.

The region contains the richest body of Aboriginal rock paintings in New South Wales.

the people of this area were first observed by the explorer Thomas Mitchell in 1835:

‘The natives of the Darling live chiefly on the fish of the river, and are expert swimmers and divers.

They can swim and turn with great velocity under water, and they can both see and spear the largest fish, sometime remaining beneath the surface a considerable time for this purpose. In very cold weather, however, they float on pieces of bark; and thus also they can spear the fish, having a small fire beside them in such a bark canoe. They also feed on birds, and especially on ducks, which they ensnare with nets, in the possession of every tribe. These nets are very well worked, much resembling our own in structure, and they are made of the wild flax, which grows in tufts near the river … Fishing nets are made of various similar materials, being often very large; and attached to some of them, I have seen half-inch cordage, which might have been mistaken for the production of a rope-walk. But the largest of their nets are those set across the Darling for the purpose of catching the ducks which fly along the river in considerable flocks. These nets are strong, with wide meshes; and when occasion requires, they are stretched across the river from a lofty pole erected for the purpose on one side, to some large opposite tree on the other … The native knows well “the alleys green” through which at twilight,, the thirsty pigeons and parrots rush towards the water; and there, with a smaller net hung up, he sits down, and makes a fire ready to roast the birds, which may fall into his snare.’

Mitchell found that, along the Darling, seed harvesting was extensively practised by the Aborigines:

‘In the neighbourhood of our camp the grass had been pulled, to a very great extent, and piled in hay-ricks… At first, I thought the heaps were only the remains of encampments, as the Aborigines sometime sleep on a little dry grass; but when we found the ricks, or hay-cocks, extending for miles, we were quite at a loss to understand why they had been made.’

It was not until on another expedition in 1846, when on the Macquarie River, that Mitchell learned the true purpose of the grass gathering:

‘Mr Kinghorne [an early settler] now informed me that it was called by the natives “cooly”, and that the [women] gather it in great quantities, and pound the seeds between stones with water, forming a kind of paste or bread; thus was clearly explained the object of those heaps of this grass which we had formerly seen on the banks of Darling. There they had formed the native’s harvest field.’

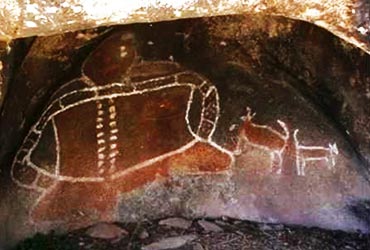

ABORIGINAL ROCK ART. BUNJIL’S CAVE-GRAMPIANS, WESTERN VICTORIA.

Bunjil is widespread in the Aboriginal mythology of south-east Australia. He was seen as a supreme, God-like figure; benevolent, old and wise; and the maker of the earth, trees, animals and man.

The linking of this site with Bunjil is based upon a passage from Naitve Tribes of South-East Australia by the anthropologist A.W. How which as published in 1904:

‘… one of the Mukjarawait [name of an Aboriginal tribe] said that at one time there was a figure of Bunjil and his dog painted in a small cave behind a large rock in the Black Range near Stawell.’

Today Bunjil can be seen in the same Black Range (not to be confused with the Black Range west of the Grampians) squatting alongside his two native dogs, the forehalf of one of which is depict on the right hand side of the stamp.

The style of painting at this site is unique n Victoria, Being quite different to small, simple paintings that occur throughout the rest of the Grampians and in the western Black range.

The natural bounties available to the Aborigines in this area are described by an early squatter, Charles Browning Hall, who in 1841 had taken up Mokepille Run at the foot of Mt. William in the Grampians:

‘Herds of kangaroo abounded in the forests, and emus grazed over the plains, in some cases so tame as to approach the rider with a strange gaze of curiosity.

the creeks were then all fringed with reeds and rushes, undevoured by hungry cows and gaunt working bullocks. These reeds and rushes formed a beautiful edging to the dark solemn pools overhung by the water-loving gum-trees, where wild fowl abounded, as the plains did with quail and turkeys.’

Hall also has left us some information concerning the local Aborigines:

‘About the Grampians [the Aborigines] were numerous at the time of my residence, and had apparently been much more so, judging from the traces left by them in the swampy margins of the river. At these places we found many low sod banks extending across the shallow branches of the river, with apertures at intervals, in which were placed long, narrow, circular nets (like a large stocking) made of rush-work. Heaps of muscle [sic] shells were also found abounding on the banks, and old mia-mias where the earth around was strewed with the balls formed in the mouth when chewing the [starchy] matter out of the bulrush root.

They had the art here of catching birds with a long slender stick like a fishing rod, at the end of which was a noose of grass twisted up. With this apparatus and a screen of boughs, They succeeded in putting salt on birds’ tails to some purpose.’

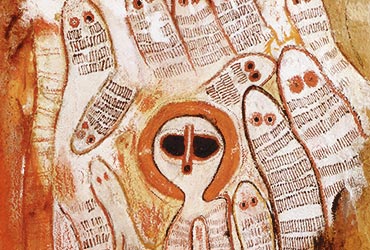

ABORIGINAL ROCK ART. QUINKAN GALLERY-CAPE YORK, QUEENSLAND

In a belief sandstone country west of Cooktown there is a concentration of hundreds of rock galleries. They are mostly situated on or near the top of escarpments, 200 to 500 meters above the floors of the main river valleys. Although these rock shelters were visited all year round, they were mainly occupied during the wet season from November to April when the rivers are in flood and the mosquitoes bad in the low country. During the dry winter months the family groups camped in the sandy river beds and the fish, tortoises and other life in the isolated water holes formed an important part of their diet. The discovery of gold in the region in the 1870’s, and subsequent plagues of pneumonic influenza and other European diseases, have led to the virtual disappearance of the the tribes who once inhabited the region.

One such gallery, a portion of which is depicted on the stamp, contains a predominance of Quickens, the spirit figures which are said to be suggestive of things ‘bad’, as opposed to the ‘good’ ancestral beings painted in other shelters. The supernatural origin of the Quickens can be identified by their possessing some non-human featured and distortions of body, limbs and head.

Percy Trezise, the ‘discoverer’ of most of the shelters, was told by an old Aborigine that the large elongated figure was a Quinkan called Timara. There is a tradition that Timara is an ancestral being responsible for distributing food supplies about the country. Other traditions have the Quickens as ghosts of the dead to be feared and avoided.

The explorer Ludwig Leichhardt has left us a description of the contents of a camp of the Aborigines when he passed near the region in 1845:

‘Tree columns (vessels of stringy bark) were full honey water… Dillis [woven bags], fish spears, a roasted bandicoot, a pecies of potatoes [sic], wax, a bundle of tea-tree bark with dry shavings; several flints fastened with human hair to the ends of sticks,and which are used as knifes to cut their skin and food; a spindle to make strings of opossum wool; and several other small utensils, were in their camp.’

Leichhardt found huts which he thought were contracted to keep the occupants high and dry during the rainy season:

‘We saw a very interesting camping place of the natives, containing several two-storied [sic] gunnies, which were contracted in the following manner: four large forked sticks were rammed into the ground, supporting cross poles played in their forks, over which bark was spread sufficiently strong and spacious for a man to lie upon; other sheets of stringy-bark were bent over the platform, and formed an arched roof, which would keep out any wet. At one side of these constructions, the remains of a large fire were observed, with many mussel shells scattered about. All along the Lynd we had found the gunnies of the natives made of large sheets of stringy-bark, not however supported by forked poles, but bent, and both ends of the sheet stuck into the ground; Mr. Gilbert thought the two-storied [sic] gunyas were burial places; but we met with them so frequently afterwards, during our journey round the gulf, and it was frequently so evident that they had been recently inhabited, that no doubt remained of their being habitations of the living, and constructed to avoid sleeping on the ground during the wet season.’

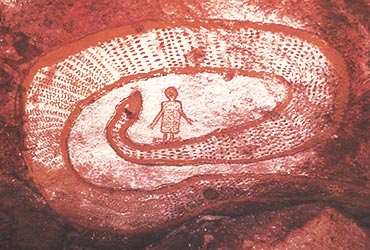

ABORIGINAL ROCK ART. WANDJINA ART-THE ROCK PYTHON AT GIBB RIVER-THE KIMBERLEYS, WESTERN AUSTRALIA

The spectacular Wandjina art of the Kimberleys, Western Australia,is represented by the legend of the Rock Python at Gibb River. Depicted on the stamps are portions of a larger painting which is located in a cave not many miles from Gibb River Station.

The story of this site has been passed on as follows. The rock python came from the east on a route heading towards the sea. The snake was travelling with its babies, and the whole party was very tired, the babies crying loudly. The cave provided a welcome resting place, so they decided to live there, a Wandjina spirit providing them with assistance. The place is called Mandangari - belonging to the Manda - and is a totem for people from that area.

The first European account of Wandjina art was given by the explorer George Grey who, in 1838, was travelling through the Kimberleys looking for a supposed great western river:

‘Finding that it would be useless to lose more time in searching for a route through this country, I proceeded to rejoin the party once more; but whilst returning to them, my attention was drawn to the numerous remains of native fires and encampments which we met with, till at last, on looking over some bushes, at the sandstone rocks which were above us, I saw suddenly from one of them a most extraordinary large figure peering down upon me. Upon examination, this proved to be a drawing at the entrance to a cave, which, on entering, I found to contain, besides, many remarkable paintings …

On this sloping roof, the principal figure which I have just alluded to, was drawn; in order to produce the greater effect, the rock about it was painted black, and the figure itself coloured with the most vivid red and white. It thus appeared to stand out from the rock; and I was certainly rather surprised at the moment that I first saw this gigantic head and upper part of a body bending over and staring grimly down at me.’

The Aborigines believe the Wandjina spirits to be beings in the clouds. They once travelled the earth like people, then entered the earth at places where their images are left on rock. Initially these images were created by Wandjinas themselves, and the humans have inherited the responsibility for maintaining them. The image is cloud and lightning, great eyes and a mysterious emptiness where a mouth might have been.

Ian Crawford, an archaeologist and documenter of Wandjina art, has described how he saw an Aborigine paint:

‘…the artists prepare a white background and apply their coloured ochres over this. The white background is prepared in the following way. The artist finds a flat stone to use as a grinding dish, and on this he rubs the ache while adding water. When he has obtaind a fairly large quantity of paint, he dips… Over the white background, the red, yellow or black lines of the paintings are applied: thick lines by finger and fine lines by brush.’

Crawford gives an account of the traditional power of the Wandjinas:

‘Although the paintings represent the bodies of the dead Wandjinas, the spirits of the Wandjinas live on in much the same way as the Aborigines believe the spirits of human beings continue to exist after their death. These Wandjina spirits have considerable powers and the Aborigines are careful to observe a certain amount of protocol when they approach the paintings, fearing that if they do not, the spirits might take their revenge. This protocol normally consists of calling out to the Wandjinas from several yards distance, to tell them that the party is approaching and will not harm the paintings…

Should the Wandjinas be offended, the Aborigines believe that they will take their revenge by calling up the lightning to strike the offender dead, or the rain to flood the land and drown the people, or the cyclone with its gales which devastate the country.’

The snake images and the Wandjinas are closely associated, often in a way that makes it difficult to know where the idea of one ends and the other beings. They are both painted in the same style, an outline with decorations on a white ground; they are both associated with the weather, spirit children and fertility.

Grey described the nature of the country in which the local Aborigines lived. The time of year was at the end of the rainy season:

‘…we reached the extremity of the sandstone ridges, and a magnificent view burst upon us. From the summit of the hills on which we stood, an almost precipitous descent led into a fertile plain below; and from this part, away to the southward, for thirty to forty miles, stretched a low luxuriant country, broken by conical peaks and rounded hills, which were richly grassed to their very summits. The plains and hills were both thinly wooded, and curving lines of shady trees marked out the courses of numerous streams. Since I have visited this spot, I have traversed large portions of Australia, but have seen no land, no scenery to equal it.’

Continuing on, Grey came upon a camp of the Aborigines:

‘We Halted for breakfast … under the shade of a large group of the pandanus. This was evidently a favourite haunt of the natives, who had been feeding upon the almonds which this tree contains …, and to give a relish to their repast had mingled with it roasted unios, or fresh-water muscles [sic], which the stream had produced in abundance.’

ABORIGINAL ROCK ART. ‘X-RAY’ STYLE ART - KAKADU NATIONAL PARK, ALLIGATOR RIVERS AREA, NORTHERN TERRITORY

In 1845, when the explorer Ludwig Leichhardt was making his way into Arnhem Land from the south, one of his men came to him with news of his sighting a fresh-water turtle ‘depicted with red ochre on the rock’. This region is known to contain what is probably the most well-known style of all the various Aboriginal art styles found throughout Australia, the X-ray art of western Arnhem Land.

An important animal known to the Aborigines of Arnhem Land is the silver barramundi, or ‘namangol’ to the people of the Djawonj language group. The silver barmaid is a fine example of the X-ray style of painting which is characteristic of this region. In fact, the silver barramundi is drawn in a particular style of X-ray art known as the descriptive style, with the external features as well as the internal organs and bone structure of the animal, represented in considerable detail.the other animal depicted in X-ray style is ‘djorrkun’, the rock possum. This design is portrayed in the decorative version of X-ray art, where the animal is subdivided and infilled by lines for purely decorative purpose. Djorrkun was also painted in the territory of the Djowonj language group.

Leichhardt’s description of the country as he came into the valley of South Alligator River conjures up an image of a land of plenty for the Aborigines:

‘The river gradually increased in size, and its bed became densely fringed with Pandanus; the hollows and flats were covered with groves of drooping tea-trees. Ridges of sandstone and conglomerate approached the river in several places, and at their base were seen some fine feed and rushy lagoons, teeming with water-fowl…The natives were very numerous, and employing themselves either in fishing or burning the grass on plains, or digging for roots… The cackling of gees, the quacking of ducks, the sonorous note of the native companion [brolga], and the noises of black and white cockatoos, and a great variety of other birds, gave to the country, both night and day, an extraordinary appearance of animation’

Further on , as he approach the East Alligator River he found the Aborigines actively engaged:

‘The natives were remarkably kind and attentive, and offered us the ring of rose-coloured Eugenia apple, the cabbage of the Seaforthia palm, a fruit which I did not know, and the nut-like swelling of the rhizome of either a grass or a sedge. The last had a sweet taste, was very mealy and nourishing, and the best article of the food of the natives we had yet tasted. They called it “Allamurr”, and were extremely fond of it. The plant grew in depressions the plains, where the boys and young men were occupied the whole day in digging for it. The women went in search of other food; either to the sea-coast to collect shell-fish, - and many the broad paths which led across the plains from the forest land to the salt-water - or to the brushes to gather the fruits of the season, and the cabbage of the palms. the men armed with a woman [spear-thrower], and with a bundle of goose spears, made of a strong reed o bamboo, gave up their time to hunting. It seemed that they speared the geese only when flying; and would crouch down whenever they saw a flight of them approaching: the geese, however, knew their enemies so well, that they immediately turned upon seeing a native rise to put his spear into the throwing stick. Some of my companions asserted that they seen them hit their object at the almost incredible distance of 200 yards.’

Leichhardt’s description of the valley of the East Alligator River is evidence of why the area is now a national park:

‘… we found a passage between the lagoons, and entered into a most beautiful valley, bounded on the west, east, and south by abrupt hills, ranges, and rocks rising abruptly out of an almost treeless plain clothed with the luxuriant verdure, and diversified by large Nymphaea lagoons, and a belt of trees along the creek which meandered through it.’

As Leichhardt gained the coast, he noticed the Aborigines had devised food gathering techniques appropriate to that environment:

‘The natives now became our guides, and pointed out to us a sound crossing place of the creek, which proved to be the head of the salt-water branch of the East Alligator River. We observed a great number of long conical fish and crab traps at the crossing place of the creek and in many of the tributary salt-water channels.’

X-ray art is still widely practised in Arnhem Land but most commonly on bark; it is thought that the last rock art was executed in 1963 at Nourlangie Rock in what is now Kakadu National Park. Kakadu is Aboriginal land which has been lead back to the nation for all Australians to enjoy.

PHOTO HEADER: Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory.

PHOTO 1: Lightning Man Stormmaker, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory.

PHOTO 2: Wandjina in the Wunnumurra Gorge, Barnett River, Kimberley, Western Australia.

PHOTO 3: Rock engravings, Mount Cameron West, North-west Tasmania.

PHOTO 4: Rock engravings, Mount Cameron West, North-west Tasmania.

PHOTO 5: Stick figures, Cobar region, New South Wales.

PHOTO 6: Cave paintings, Mount Grenfell, Cobar region, New South Wales.

PHOTO 7: Bujil's Cave, Grampians, Victoria.

PHOTO 8: Quinkan Gallery, Cape Yourk, Queensland.

PHOTO 9: Quinkan Gallery, Cape Yourk, Queensland.

PHOTO 10: The rock python at Gibb River, the Kimberleys, Western Australia.

PHOTO 11: The rock python at Gibb River, the Kimberleys, Western Australia.

PHOTO 12: Wandjina spirit and snake babies at Gibb River, the Kimberleys, Western Australia.

PHOTO 13: Wandjina spirit and snake babies at Gibb River, the Kimberleys, Western Australia.

PHOTO 14: Silver barramundi, 'namangol', Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory.

PHOTO 15: Turtle, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory.

PHOTO 16: Kangaroo, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory.

PHOTO 17: Rainbow Serpent, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory.

PHOTO 18: Man, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory.

SOURCE: Berndt, R.M., Berndt, C.H. and Stanton, J.E. Aboriginal Australian art. Sydney, Methuen Australia, 1982.

Crawford, I.M. The art of Wandjina. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1968.

Godden, E. and Malnic, J. Rock paintings of Aboriginal Australia. Sydney, Reed, 1982.

Gunn, R.G. Banjil's Cave. Melbourne, Victoria Archaeological Survey, Ministry for Conservation, 1983. (Occasional reports series no13).

Trezise, P.J. Quinkan country. Sydney, Reed, 1969.

READ MORE: