THE FIRST AUSTRALIANS

BACK

Pre-history

There are those amongst the Aborigines who pass on the tradition that their people have always lived in Australia, since the beginnings of the human race. They identify their

origins with the very land itself.

Archaeologists generally accept that the Aborigines came to Australia more than 50,000 years ago when the level of sea was over 100 metres below its present level. Even then, this would have entailed a short sea voyage as there was never a complete landbridge between Asia and Australia. The oldest scientifically dated site occurs at 39,500 years before the present. The antiquity of this campsite on the Upper Swan River, Western Australia, is followed by further confirmations of human occupation in the Willandra Lakes region of New South Wales. Mussel shell refuse with evidence of cooking at Lake Outer Arumpo is dated to 35,500 years, while at Lake Mungo several sites containing shells and stone tools are dated at beyond 30,000 years. By the end of ice age, about 18,000 years ago, the Aborigines had left evidence of their presence at about thirty known sites encompassing a wide variety of environments. they had inhabited coastal plains, lived within sight of glaciers in southern Tasmania, hunted among the escarpments of Arhem Land and penetrated the arid Nullarbor Plain.

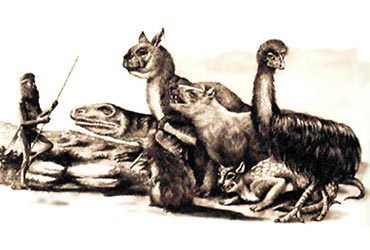

Through the efforts of archaeologists, we know something of ice age people. We know they made use of fire, ground up ochre pigments for decoration, wore ornaments and honoured their dead. They shared the land with a range of huge marsupials. Gint kangaroos, of which the largest, Procoptodon goliah, stood three metres tall, browsed upon the herbage. Other animals encountered by Aborigines were giant emu-like birds, large echidnas and wombats, and other less familiar forms such as the Diprotodon, a rhinoceros-sized wombat-like creature, which was the largest marsupial that ever lived. Carnivores, such as the marsupial lion (Thylacoleo) and marsupial wolf, the latter surviving into very recent times as Tasmanian Tiger, were also part of this ancient landscape.

About 18,000 years ago the climate began to warm up. As the polar ice caps melted, the sea started to rise, beginning a period of encroachment upon the land which would result in Australia being separated from New Guinea, and Tasmania being cut off from the mainland. As evaporation rates increased, inland lakes contracted or dried up. The giant marsupials apparently disappeared at this time.

The Aborigines adapted to these changes: at Lake Mungo, archaeologists have recorded a transition to seed grinding economy as the lake dried up.

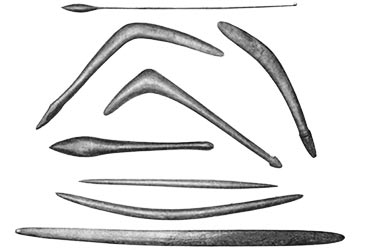

By about 10,000 years ago climatic conditions had settled down to something like what we experience today. The Aborigines had now supplemented their toolkit with more specialised implements. Barbed spears, the spear-thrower and the boomerang now make their appearance. By 4000 years ago this trend had resulted in a proliferation highly specialised stone tools, the exact purpose of many of which elude archaeologists. They were mostly lightweight items with highly finished cutting edges; hence the naming of the late phase of mainland Aboriginal culture as the ‘small tool tradition’. A comparison with tools from the earlier ice age shows that the Aborigines had now achieved substantial improvement in their efficiency.

Then about 2000 years ago in south-eastern Australia further changes took place in the Aboriginal toolkit. Simple quartz flakes appear to have replaced many of the carefully finished earlier items and there was a greater use of bone and shell for tool making to the extent that some later sites are almost devoid of stone tools. Shell fish-hooks make their first appearance along with the multi-pronged fish-spear which is reflective of a more intensive exploitation of marine resources at this time. Some scholars have suggested that these changes may have been in response to a restriction in foraging areas induced by population pressures.

The Aboriginal population of Australia before European settlement, on the basis of population densities encountered by the explorers and other early observers, had been thought to number about 300,000 people. However, there is evidence that prior to these observations, the Aborigines had been visited by smallpox epidemics, thought to have originated from the early east coast European settlements after 1788. Major Thomas Mitchell, exploring along the Lachlan and Darling Rivers of New South Wales in the 1830’s, noted pock-marks on the Aborigines and was frequently told by them that the tribes had once been numerous. At one point on the Darling he rode to the top of a lonely hill and found ‘three large tombs’. I could scarcely doubt, that these tombs covered the remains of that portion of the tribe, swept off, by the fell disease, which had left such marks on all who survived.’ Captain Charles Sturt observed the depredations of small-pox during his exploration down the Macquarie River to the Darling in 1829. ‘As his tribe gathered round him, the old chief threw a melancholy glance upon them, and endeavoured, as much as he could, to explain the cause of that affliction which, as I had rightly judged, weighed heavily upon him. It appeared, then, that a violent cutaneous disease raged throughout the tribe, that was sweeping them off in great numbers.’ And again: ‘They seemingly occupy permanent huts, but their tribe did not bear any proportion to the size or number of their habitations. It was evident their population had been thinned.’ Based on the recorded results of this disease upon other people, where devastating effects were observed on the North American Indian tribes, some of which were reduced to extinction, a recent researcher has proposed that the estimate of 300,000 is a serious understatement of the 1788 Aboriginal population. Professor Noel Butlin, a noted economic historian, shows that, following smallpox epidemics and venereal disease, Aboriginal population may have declined to 20% of their former levels by the time the first estimates were made in 1830’s.

PHOTO HEADER: The First Australians.

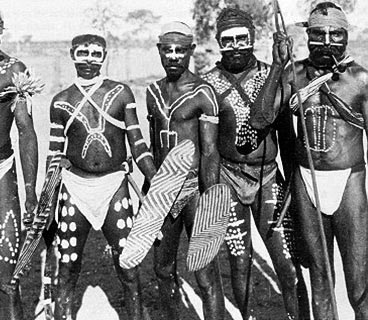

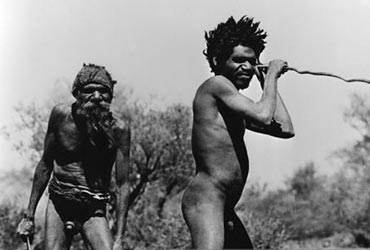

PHOTO 1: Indigenous Australians.

PHOTO 2: The megafauna of Australia compared to an adult male human.

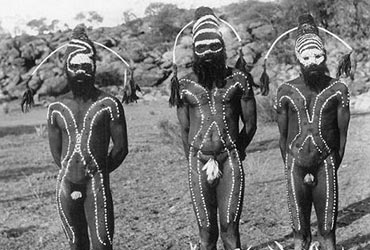

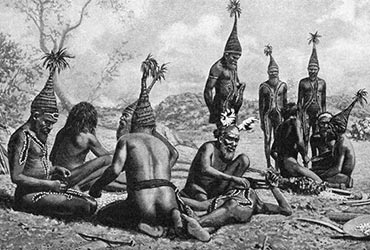

PHOTO 3: Aboriginal men in body paint and headdresses.

PHOTO 4: Traditional Aboriginal weapons and tools.

PHOTO 5: Aboriginal men hunting for a kangaroo.

PHOTO 6: Aborigines Apply Ceremonial Body Paint.

SOURCE: Bourke, C., Johnson, C. and White, I. Before the invasion; Aboriginal life to 1788. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1980.

Built, N.G. Our original aggression; Aboriginal populations of south-eastern Australia 1788-1850. Sydney, Allen and Unwin, 1983.

Clark, J. The Aboriginal people of Tasmania. Hobart, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 1983.

Flood, J. Archaeology of the Dreamtime. Sydney. Collins, 1983.

READ MORE: