HOW THE ABORIGINES LIVED

BACK

What we know about Aboriginal society has been pieced together from a variety of sources and although the pictures is at times cloudy, research is continually adding to our

knowledge.

Occasionally Aborigines wore cloaks of possum or kangaroo skins, but more generally they went about naked, even during the harsh winters of the south. Mitchell’s guide, Piper, mocked the white members of the expedition for encumbering their bodies with clothes and blankets and shivering through wintry nights when all he needed was a small fire to his naked body. The following entry from Mitchell’s journal was recorded near Mount Hope, just south of Murray on 21 June 1836. ‘At this camp, where we lay shivering for want of fire, the different habits of the aborigines and us, strangers from the north, were strongly contrasted. On that freezing night, the natives, according to their usual custom, strip off all their clothes, previous to lying down to sleep in the open air, their bodies being doubled up around a few burning reeds. We could not understand how they could lay thus naked, when the earth was white with hoar frost; and they were equally at a loss to know, how we could sleep in our tents without a bit of fire to keep our bodies warm.’ When required, skins were sewn together with animal sinews applied with a pointed bone awl and decorated with incised designs. Body ornamentation was effected with necklaces of bone and tooth; reeds and teachers supplied hair adornments; bones placed through the nose decorated the face; and colours were applied to the skin with the various ochre pigments.

The Aborigines drew their living from the land in a variety of ways. The diversity of hunting and gathering techniques matched the variability of environments found throughout Australia. In suitable places they constructed, in stone and brush, fish and eel traps to take advantage of seasonal migrations and the fluctuating water levels. They caught waterfowl by placing nets across rivers and then inducing the birds to take a low flight path by means of a simulated hawk attack from a released boomerang. They caught the emu by climbing the native cherry, dropping its fruit to the ground and waiting concealed in a hut in the branches, sure in the knowledge that any passing birds would not be able to resist their favourite food without stopping. The women gathered with their digging sticks the yellow daisy yams which were roasted and eaten in large quantities. In the dry season fish were efficiently farmed from inland waterholes by administering a poison which brought the stupefied fish to the surface where they were easily gathered. in 1828, on the Macquarie River in New South Wales, Sturt witnessed an alternative, and no less successful, fishing technique of the Aborigines. ‘As they were treated with kindness, the natives who accompanied us soon threw off all reserve, and in the afternoon assembled at the pool below the fall to take fish. they went very systematically to work, with short spears in their hands that tapered gradually to a point, and sank at once under water without splash or noise with the fish they had transfixed; the others remained about a minuter under water, and then made their appearance near the same rock into the crevices of which they had driven their prey. Seven fine bream were taken, the whole of which they insisted on giving to our men, although I am not aware that any of themselves had broken their fast that day.’

In the tropical north of Australia a sample of foodstuffs might include sharks, crocodiles, shell fish, kangaroos, snakes, grubs, ducks roots, wild bananas and honey. Here the dugong would be harpooned from a canoe and before the animal could escape the hunter would quickly close its breathing holes with wooden plugs, thus choking it. In arid regions the art of finding water was a highly developed skill.

Aborigines dug for the long roots of the male tree which lay just below the surface and which, when broken into short pieces, released drops of clear water.

Goods were traded across the continent in a succession of transactions. Pearl shell from the north-west coast was worn by Aborigines in coastal South Australia. Baler shell from Cape York found their way to the Flinders Ranges. Stone axe heads, quarried and roughed at Mt.William near Lancefield in Victoria, have been found as far away as 800 kilometres. Even grater distances were covered by stone axes from Moore Creek near Tamworth in New South Wales. As an idea of the time element involved in effecting a passage through the trade network, it is recorded that a corroboree, which was first performed in north-west Queensland, appear 25 years later on Great Australian Bight, a distance of 1600 kilometres.

The Aborigines moved about their territories in small numbering from about twenty to fifty. At the start of each day the men would separate into game hunting parties while the women and children would seek out more reliable supplies of edibles such as roots, berries and any small animals they could kill. All would have pre-arranged the location of the next camp site, upon arriving at which, the food from the day’s activities would be roasted and shared around. If the men were unsuccessful, the whole group depended upon the exertions of the women. One of the latter’s woven bags was examined in central Victoria during winter in 1836. It contained three snakes, three rats, about a kilogram of small fish, like white bait, cray fish, and a quantity the roots of the yellow daisy yam. Apart from the foodstuffs, the bag also contained, ‘various bodkins and colouring stones, and two logos or stone hatchets’.

In general, the more productive the environment in which the Aborigines lived, the more substantial were their habitations.The remains of stone houses have been found at Lake Condah in Victoria in association with an eel trap system that would have been productive for perhaps six month of the year. Sturt , on the Darling River in New South Wales in 1829, observed: ‘Early in the day, we passed a group of seven huts, capable of holding from twelve to fifteen men each. They appeared to be permanent habitations, and all of them fronted the same point of the compass. In searching amongst them we observed two beautifully made nets, of about ninety yards in length. the one had much larger meshes than the other, and was, most probably, intended to take kangaroos; but the other was evidently a fishing net’. Mitchell in 1835, and several hundred kilometres further down the same river, observed village of ‘permanent huts’ in association with numerous and well beaten paths. Late in 1836, Captain John Hepburn in the first wave of overlanders into the ‘interior’ , recalled: ‘Still keeping the Major’s line on a creek running into the Goulburn, we came on a very large encampment, about 70 mia-mias, but all the natives fled on our approach, leaving their fires burning; also a specimen of their knowledge of naval architecture, in the shape of canoe about 12 feet in length, cut rudely from a half round of a box tree, whitewash bent, and gave the canoe a good spring at both ends. This sheet of bark would carry four men easily’. Ludwig Leichhardt, in Arnhem Land in 1845, found ,’fine camp of like huts, covered with tea-tree bark’.

No aspect of Australian Aboriginal culture is more conspicuous to the casual observer than ceremonial dance, in some parts of Australia referred to as ‘corroboree’. It was usually performed in the evenings, and for a variety of reasons: as a mark of respect for a visiting group, to celebrate a victory over a rival group, a successful hunt, cementing of a relationship at the end of a conflict, a conflict, a marriage or often just for sheer pleasure. Body art was an integral part of these dances. Various motifs, using charcoal and a mixture of acres, pipe clay and animal fats, were applied with the fingers, white were complemented with decorations of grass, leaves and feathers. One such corroboree was witnessed in central Victoria in 1843, an abridged version of which is given below. The viewer has left us a glimpse of those nightly scenes that hitherto had regularly enlivened the Australian bush at a thousand campsites. ‘I had witnessed corroborees inSydney. Adelaide and Queensland, and I can safely say that it equalled anything that ever I saw … Having arrived some minutes before the corroboree commenced we could see dark forms about, some with firesticks and spears, flashing them before the serpent with the velocity of lightning, while further in the background in the dark a wild unearthly concentrated scream of about 1000 voices would make your blood curdle, and the scream would be answered immediately in the opposite direction by a similar series of yells, the beating of the nulla-nullas and boomerangs as an accompaniment formed the orchestra, while the lighting of a large fire near the serpent served for the raising of the curtain … After a while the females old and young in alternate rows, sidled over to where the musicians were and sat down and all raised their voices in the chorus.’ The viewer describes how this was kept up until out the darkness emerged a procession of painted Aborigines in single file making towards the fiercely burning fire. Every ten yards they gave a shout and this, combined with the chanting and beating of the nulla-nullas,’made a singular pandemonium’/ ‘Many of them had their hair all stuck up with parrots’ and cockatoos’ feathers. No two of them were painted exactly alike and in some instances they were most artistically done up.’

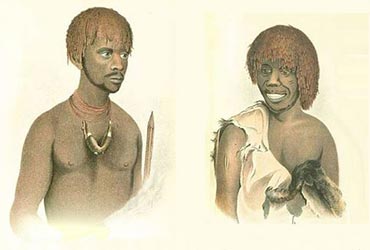

The Tasmanian Aborigines

For 12,000 years the curly-haired Tasmanians had been separated from their brethren on the mainland. After the rising of the seas, Tasmanian Aboriginal culture apparently for a time followed trends in motion since the ice age. Stone tools continued to become smaller and better worked; bone implements were commonplace. Then by 3000 years ago fish had been dropped from the diet. By the same time the Tasmanians had ceased the manufacture of tools made of bone, a source which had once provided up to a third of their tool material. One possible explanation is that the bone tools were used in manufacture of fishing nets and there was either a loss of the knowledge of net manufacture or a switch from fish catching to a more productive hunting activity such as seal or abalone. By the time of the arrival of Europeans, the material culture of the Tasmanians was restricted to about two dozen items which may have been indicative of greater specialisation in their ‘means of production’. They followed a similar hunter-gatherer lifestyle to the mainlanders, were concentrated along the coastline and lived in shelters thatched with bark, grass or turf. The men here were in the habit of decorating their hair with a mixture of orange ochre and animal fat, a practice also in vogue amongst the Aborigines of Gippsland in Victoria.

PHOTO HEADER: Aboriginal men making a shield using the bark from the mangrove tree.

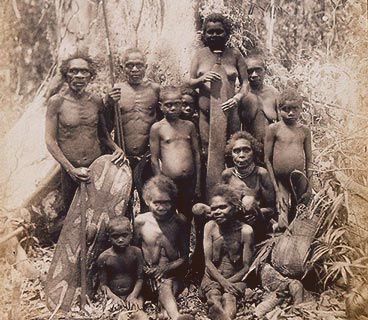

PHOTO 1: Rainforest Aboriginal people.

PHOTO 2: Aboriginal man sitting in front of a hut.

PHOTO 3: A young Aborigine spears a fish while his friends hunt for turtles in the Northern Territory of Australia.

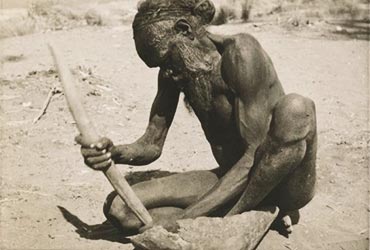

PHOTO 4: Aboriginal man hollowing out a wooden dish with a stone adze, central Australia.

PHOTO 5: Women and childreen setting out to go food collecting, Western Desert, Western Australia.

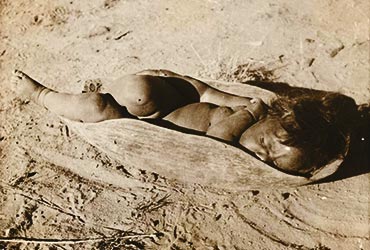

PHOTO 6: Aboriginal baby asleep in a wooden bowl.

PHOTO 7: Aboriginal traditional food - Wichetty Grubs.

PHOTO 8: Bush tucker - wild plants, nut, and berries.

PHOTO 9: Tasmanian Aborigines.

PHOTO 10: Group of Natives of Tasmania.

SOURCE: Bourke, C., Johnson, C. and White, I. Before the invasion; Aboriginal life to 1788. Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1980.

Built, N.G. Our original aggression; Aboriginal populations of south-eastern Australia 1788-1850. Sydney, Allen and Unwin, 1983.

Clark, J. The Aboriginal people of Tasmania. Hobart, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 1983.

Flood, J. Archaeology of the Dreamtime. Sydney. Collins, 1983.

Bride, T.F. ed. Letters from Victorian pioneers. South Yarra, Vic., Currey O’Neil, 1983. 1st pub. Govt Printer for the Trustees of the Public Library, 1898. John Hepburn p.57-83; Charles Hall p.260-276.

Grey, G.E. Journals of two expeditions of discovery in north-west and Western Australia, during the years 1837, 38 and 39. Adelaide, Libraries Board of South Australia, 1964. 1st pub. London, Boone,1841. 2v.

Leichhardt, F.W.L. Journal of an overland expedition in Australia from Moreton Bay to Port Essington. Sydney, Doubleday, 1982. 1st pub. London, Boone, 1847.

Mitchell, T.L. Three expeditions into the interior of eastern Australia. 2nd edn. Adelaide, Libraries Board of South Australia, 1965. 1st pub. London, Boone, 1839. 2v.

Mitchell, T.L. Journal of an expedition into the interior of tropical Australia. New York, Greenwood Press, 1969. 1st pub. London, Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1848.

Sturt, C. Two expeditions into the interior of southern Australia. Sydney, Doubleday, 1982. 1st pub. London, Smith, Elder, 1833. 2v.

READ MORE: